The extension of this rule is that in a movie, any important plot point or crucial information must be seen by the audience. In a play, its perfectly acceptable for a minor character to report that Hamlet's ship has been attacked by pirates; in a movie we'd better have a scene where we see the pirates attack. Or if there's some important event in the lead character's past, don't just have people talk about it- show a flashback.

That being said, every rule has its exception. The sci-fi site io9 had some articles a few months back, "5 situations where its better to tell than show in your fiction" and "20 great infodumps from science-fiction novels", which focus on notable "infodumps" in sci-fi novels. Lately, I've been thinking about instances where movies have successfully broken the cardinal "Show, Don't Tell" rule.

And so, although most good movies subtly parse out exposition through action and dialogue, here's six examples of movies that effectively broke the rules and quickly spelled everything out in massive infodumps:

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001): Opening Sequence

The Infodump: If there's one thing J.R.R. Tolkien excelled at, it was world building. So how do you condense a 1000-page epic and an entire Silmarillion's worth of backstory into three movies? Well, Peter Jackson begins with the simplest and most direct route to backstory: have a narrator explain everything you need over an opening montage.

|

| The first of about 9,000 gratuitous close-ups of rings. |

Why It Works: For most movies, this would be a clumsy and terrible way to open the film, but the mythopoetic nature of Tolkien's novels lends itself to this type of storytelling. In a few minutes, we learn about Middle Earth and all its races, of Sauron, the One Ring to Rule Them All, and how it ended up in Gollum's hands. Thanks to the Norse-saga inspired tone of Tolkien's story, Peter Jackson's iconic visuals and Cate Blanchett's eerie (yet strangely alluring) voice-over, this sequence wonderfully establishes the world so we can get on with the story.

Would an opening voice-over packed with backstory work in a more contemporary setting than Middle Earth? Well, it did in...

Goodfellas (1990): Ray Liotta tells us his life story

The Infodump: "As far back as I can remember, I always wanted to be a gangster," Henry Hill (Ray Liotta) informs us after a brief opening teaser. He then spends the the next ten minutes narrating his whole life story, his motivations, and introducing us to the main characters.

Why It Works: In Adaptation, Charle Kaufman lets screenwriting guru Robert Kckee dispense some conventional screenwriting wisdom: "God help you if you use voice-over in your work, my friends. God help you. That's flaccid, sloppy writing. Any idiot can write a voice-over narration to explain the thoughts of a character." However, Martin Scorsese has made a whole career out of successfully breaking this rule, most notably in his magnum-opus Goodfellas.

Scorsese incorporates the voice-over as part of the film's aesthetic, as crucial to the feel of the whole as the pop-tune filled soundtrack or the contrasty cinematography. Without the narration, Goodfellas wouldn't be Goodfellas. The narration also serves to help us identify with the character of Henry Hill, despite all the despicable things we see him do. After all, he's talking straight to us, treating us as confidants.

The fact that the opening narration covers a lifetime of events establishes an engaging "storytelling" feel, while cuing us in to the fact that the events depicted in this movie will span many years. This is a crime epic, not a carefully observed analysis of a moment.

Ultimately, we see the world through Henry Hill's eyes, and so the direct line to his thoughts and feelings does not feel like the cheat it would if the movie were exclusively about him. The movie is as much about the various criminals Henry meets, and by spelling out Henry's backstory we can devote more attention to them. Besides, in the world of hardened gangsters, one is not likely to share much emotionally or otherwise, and so the voice-over gives us access to facets of Henry's character that would otherwise be unobservable.

This is why many of the great voice-overs in film history come from introverted or otherwise close-off characters. This is most true of Travis Bickle's voice-over in Taxi-Driver. Travis Bickle is a man of few words, with trouble connecting to other people (to say the least). His voice-over gives the audience a chilling glimpse into the mental state of the character in a way his dialogue and actions alone never would.

Now, movies also get away with voice-over because we are still seeing things as we listen. Even if the story is primarily told in an auditory fashion, we are still having a visual experience and thus it feels like a movie and not just a story someone is telling. But could a movie get away with just a voice, or even more minimally, just text?

Star Wars (1977): Opening Crawl

Text at the beginning (or even during) movies, is of course a grand tradition going back far into the silent era. Filmmaking pioneers like D.W. Griffith often employed title cards stuffed with text not only to clarify and advance the story, but also to help overcome the common prejudice that film was a mere novelty, hoping elevate film to a novelistic, literary "high" art.

|

| Back in the silent era, what was considered "high art" was more likely to be explicitly racist. |

But even in the silent era, filmmakers limited how much text would appear in one sitting. The occasional D.W. Griffith paragraph notwithstanding, most title cards kept the text as short as possible.

Star Wars opens with a typically short title card:

|

| I personally would have added a comma after 'ago.' |

This, however, is followed by a full minute and a half of onscreen text letting us know what has transpired up to this point. How does Lucas get away with it?

Why It Works: Two words: John Williams. Sure, opening crawls were a staple of the 30's serial genre that Lucas is paying homage to. But I think the real reason why the opening crawl doesn't bore us to tears is John Williams' stupendous score. It hits the right tone of fantastic, swashbuckling adventure, letting us know that what we are in store for is going to be epic and its going to be fun.

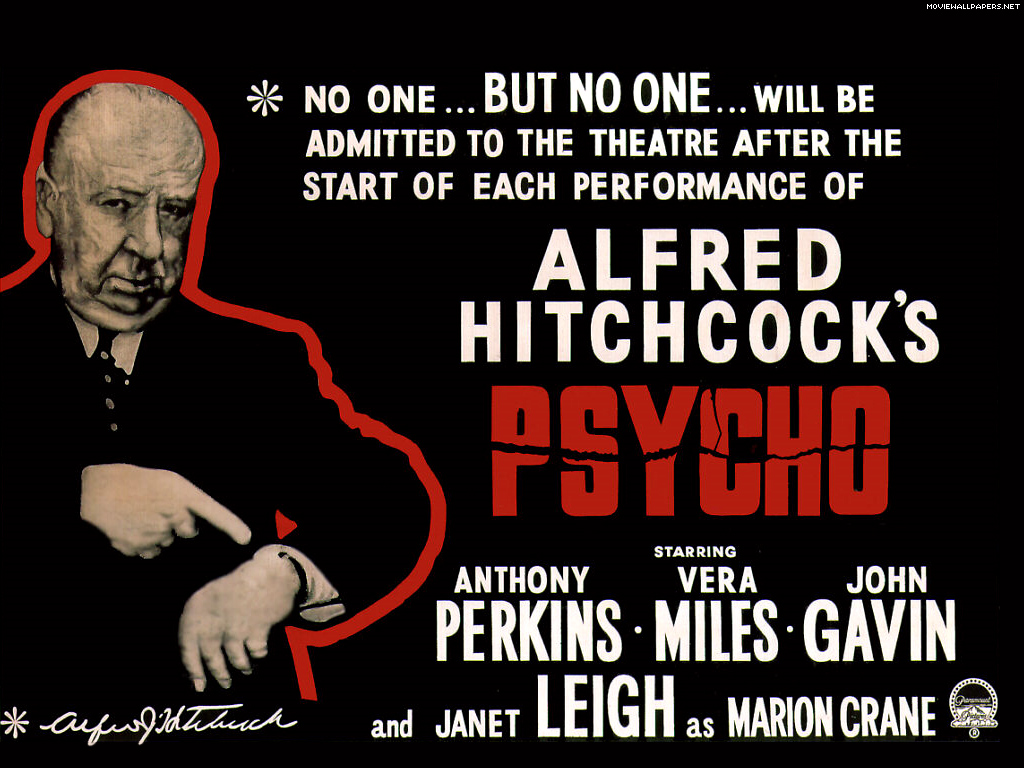

Psycho (1960): The Psychologist Explains Everything

So far I've given examples of massive infodumps at the beginning of a story. But what of the movie with so many loose ends that quick, direct exposition is needed at the end to wrap things up? Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho provides the best example. After all is said and done, a Psychologist comes out and explains exactly what the hell was going on.

Hitchcock's famous delineation between surprise and suspense has been so often repeated as to become cliche, but I think in this case its worth mentioning. Since its frequently paraphrased and bastardized, we might as well see the original quote itself:

There is a distinct difference between "suspense" and "surprise," and yet many pictures continually confuse the two. I'll explain what I mean.Hitchcock's Psycho is a prolonged experiment in blending suspense and surprise. We are in suspense because we think there's a bomb under the table; suddenly, we're surprised to find out that its not a bomb at all but something much more dangerous we weren't expecting. All the great sequences start out as a conventional Hitchcockian suspense sequence and then a surprise pulls the rug out from under our feet and shocks us. [SPOILERS FOLLOW. If you haven't seen Psycho, do yourself a favor and go rent it.]

We are now having a very innocent little chat. Let's suppose that there is a bomb underneath this table between us. Nothing happens, and then all of a sudden, "Boom!" There is an explosion. The public is surprised, but prior to this surprise, it has seen an absolutely ordinary scene, of no special consequence. Now, let us take a suspense situation. The bomb is underneath the table and the public knows it, probably because they have seen the anarchist place it there. The public is aware the bomb is going to explode at one o'clock and there is a clock in the decor. The public can see that it is a quarter to one. In these conditions, the same innocuous conversation becomes fascinating because the public is participating in the scene. The audience is longing to warn the characters on the screen: "You shouldn't be talking about such trivial matters. There is a bomb beneath you and it is about to explode!"

In the first case we have given the public fifteen seconds of surprise at the moment of the explosion. In the second we have provided them with fifteen minutes of suspense. The conclusion is that whenever possible the public must be informed. Except when the surprise is a twist, that is, when the unexpected ending is, in itself, the highlight of the story. [emphasis added]

The title or the brilliant ad campaigns promoting the film don't give anything of the plot away, and that was intentional. Its unfortunate that everyone today, even if they haven't seen the movie, knows that Janet Leigh gets murdered in the shower because that is truly one of the greatest surprises in film history.

At the beginning of the movie, audiences of 1960 would have assumed that this is a movie about Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) stealing $40,000 from her employer. The suspense is ratcheted up as she is followed by a cop and continues to flee. She gets in the shower, leaving the money sitting on the bedside dresser and leaving herself vulnerable to either the cop following her or the voyeuristic manager of the hotel, who has a peep-hole which he uses to spy upon Marion as she undresses. And then all of a sudden-

Our protagonist is shockingly murdered by an knife-wielding old lady. This is a surprise.

|

| No longer the protagonist. |

Then something extraordinary happens. With the cry of, "Mother! Oh God, mother! Blood! Blood!" coming from the Bates house, Norman Bates becomes the protagonist. We realize that Marion was murdered by Norman's domineering mother. She must be he titular psycho. As we watch him painstakingly clean up his mother's murder (throwing out the $40,000 dollars as he does) we realize that we've been following a massive red herring. The movie is not about a woman on the run who stole some money. Its about a man with maternal attachment issues who realizes his mother is a psychopathic killer. How will he deal with this situation? We want to see him wrestle with this issue, eventually reaching the peak of his character arc when he overcomes his need to protect Mother and turns her in. He's flawed, but at this point in the film he's the one who has our sympathy. We even think "Oh no!" when Marion's car, containing her body and all the evidence, stops sinking into the swamp, and we breathe a sigh of relief along with Norman when it resumes sinking.

The story continues as a suspense film as Detective Arbogast heads into the house and up the stairs. No, not up the stairs, the audience thinks, That's where Mother lives! And, as to be expected, mother murders the poor detective.

Next comes Vera Miles, Marion's sister, and Marion's boyfriend Sam Loomis. As Vera investigates the house alone (No! Not the House!) and Loomis interrogates a fidgety Norman Bates, we once again sense our sympathies realigning. Oh, I get it, we think, Norman's never going to betray his mother. He's not the protagonist, but an antagonist. Vera is the protagonist. And she's headed right for where mother is! The suspense reaches its peak when she slowly approaches the old lady sitting a basement chair. Surely, she'll spin around knife in hand. This is classic suspense. And then-

|

| SURPRISE! |

Followed by:

|

| SURPRISE! Also, WTF!?! |

So mother is corpse and Norman Bates a cross-dressing murderer. Perhaps there's some 'splainin' to do. Which brings us, at last, to:

The Infodump: All is made clear and all loose ends wrapped up by the police psychologist who explains everything using a bunch of bogus psychology that would inform Hollywood's (mis)understanding of split-personality disorder for decades .

Dr. Fred Richmond: His mother was a clinging, demanding woman, and for years the two of them lived as if there was no one else in the world. Then she met a man... and it seemed to Norman that she 'threw him over' for this man. Now that pushed him over the line and he killed 'em both. Matricide is probably the most unbearable crime of all... most unbearable to the son who commits it. So he had to erase the crime, at least in his own mind. He stole her corpse. A weighted coffin was buried. He hid the body in the fruit cellar. Even treated it to keep it as well as it would keep. And that still wasn't enough. She was there! But she was a corpse. So he began to think and speak for her, give her half his time, so to speak. At times he could be both personalities, carry on conversations. At other times, the mother half took over completely. Now he was never all Norman, but he was often only mother. And because he was so pathologically jealous of her, he assumed that she was jealous of him. Therefore, if he felt a strong attraction to any other woman, the mother side of him would go wild. [Points finger at Lila Crane] When he met your sister, he was touched by her... aroused by her. He wanted her. That set off the 'jealous mother' and 'mother killed the girl'! Now after the murder, Norman returned as if from a deep sleep. And like a dutiful son, covered up all traces of the crime he was convinced his mother had committed!He goes on to clear up every other point of potential audience confusion, including who got the $40,000 ("The swamp. These were crimes of passion, not profit.") Incidentally, this scene contains the first use of the word 'transvestite' in a Hollywood movie. The MPAA originally objected, until screenwriter Joseph Stefano argued that it was a clinical term.

Why it works: Normally, cramming all that crucial information into a speech by a newly introduced character whose sole purpose is to explain everything would be considered terrible writing. But in this case, no one cares. We go to see a movie like Psycho for the suspense and surprise, and Hitchcock has more than delivered the goods on both accounts. In my opinion, its still the best blend of suspense and surprise that Hollywood has ever come up with, and the ending remains the quintessential twist ending, one that M. Night Shyamalan wishes he could come up with.

| |

| Right now, he probably just wishes he could be the M. Night Shyamalan of ten years ago. |

The suspenseful and surprising portion of the story has ended, so now all that remains to be done is to clean up the loose ends and as quickly as possible and take a bow. Anything more would be unnecessary. We've already gotten our money's worth. And so, after we see Mother's corpse and Norman in a dress, all we need is a brief psycho-babble explanation, a final unsettling moment with Norman, a subliminal dissolve into mother's face and THE END.

Jurassic Park (1993): The Mr. DNA Film

I've you've ever read a book by Michael Crichton novel, then you know that he loves to have his scientist characters talk for pages and pages just so that he can include a bunch of interesting stuff he came across during his research (and sneak in a few whoppers along with the facts). And if you're a fan of Michael Crichton (as I consider myself to be), this is one of the things you love about him.

Readers of Jurassic Park will get to learn lots about dinosaurs, computers (circa 1989), Chaos Theory, and genetics. The section that explains how the dinosaurs were cloned lasts well over thirty pages in the book. Obviously, a movie has a more limited amount of time in which to convey the same information.

Screenwriter David Koepp uses the fact that Jurassic Park is a tourist attraction to his advantage. He lets a film-within-the-film designed for the tourists tell us all we need to know, courtesy of the friendly animated "Mr. DNA."

Why It Works: A quick, oversimplified explanation in layman's terms is exactly what you'd expect to be given to tourists- and that's all the audience needs before we're ready to move on to seeing dinosaurs. Sure, the science is bogus, but it sounds reasonable enough as explained in a spot-on parody of the educational films of yesteryear. Again, credit John Williams for a score perfectly suited to the material.

The idea of a film-within-a-film conveying essential exposition was nothing new in 1993. This is something you can trace back all the way to...

Citizen Kane (1940): News On the March

A slow approach to a gloomy old mansion where an old man lays dying. He holds a snow globe, which rolls out of his hand as he utters his last word, "Rosebud."

These moments are followed by ten minutes of fake newsreel footage, the "News on the March," summarizing the life of Charles Foster Kane.

We then are in a screening room with a bunch of reporters who were just watching the same film we were. They are challenged to find the meaning of "Rosebud," which they will attempt to do by interviewing various people who knew the Hearst-esque newspaper magnate.

|

| God bless you, Gregg Toland. |

Why It Works: As with Jurassic Park's Mr. DNA film, it helps that Welles absolutely nails the cheesy tone of 1940's March of Time newsreels (the radio counterpart of which had actually been narrated by Welles for a time). He even went to the trouble of dragging the film stock in the dirt in order to give the footage a suitable scratched appearance.

The film turns out to be just one of several competing versions of Kane's life, the others being told by his former friends and associates. All of them are somewhat unreliable narrators, and the blandness of the newsreel is a good place to start before moving to the biases of Kane's contacts. Welles and Mankiewicz's innovative script skips around through the events of Kane's life, and so having a grounding in the basic story is great way to start.

Enough has been written on Citizen Kane to fill several small libraries, so I won't say too much more, except to note that the film-within-a-film-as-exposition technique pioneered here has been copied too often to list. This is the grand-daddy of all cinematic infodumps, and perhaps greatest of them all.

No comments:

Post a Comment