In my last post, wherein I ranted about why I'm not a fan of e-books, I offhandedly referred to myself as a 'Luddite.' ["As e-readers become more ubiquitous (as I'm sure they will, despite the grumblings of Luddites like myself)..."] This led to my wife questioning me on whether that was a hypocritical thing to call myself, being as I had just posted a link to Project Gutenberg, which she viewed as me promoting the very thing I claimed to be against. So for the record, let me state two things:

1) If I link to something, I do not necessarily approve of it, nor am I trying to promote it. I consider hyperlinks to be the internet equivalent of a footnote. I use them primarily to allow curious readers to find out a little more information, while less curious readers may just continue reading.(Although in this particular case, I do happen to support Project Gutenberg.)

2) I do consider myself a Luddite in the sense that I am often resistant to new technology that changes things in a way that I perceive to be negative (and, likewise, I happily embrace technology that I view as improving things). To use one example, I steadfastly maintain that 35mm film produces a superior image to digital capture. As a professional videographer, the realities of the market have forced me to work mostly in HD since I left film school, but my preference is still to shoot film whenever possible. I have also sometimes used the term 'Luddite' to describe myself due to the fact that, despite working in a technology-dependent field, I am often the last to adopt new technologies. I tend to be stubbornly old-school in my tech habits.

This second point got me thinking about the various ways in which the term 'Luddite' is used and abused. There are several legitimate definitions for 'Luddite' which differ from each other, as well as many ways that the term is frequently misapplied. Language, of course, is infinitely malleable and constantly in flux, and so varying uses and definitions of a word are to be expected. That being said, although new uses for words are constantly being found, there are times when a word is used incorrectly. In order to clearly communicate, there must be some standard definitions. So...

What is a Luddite?

First, let's ask the Internet.

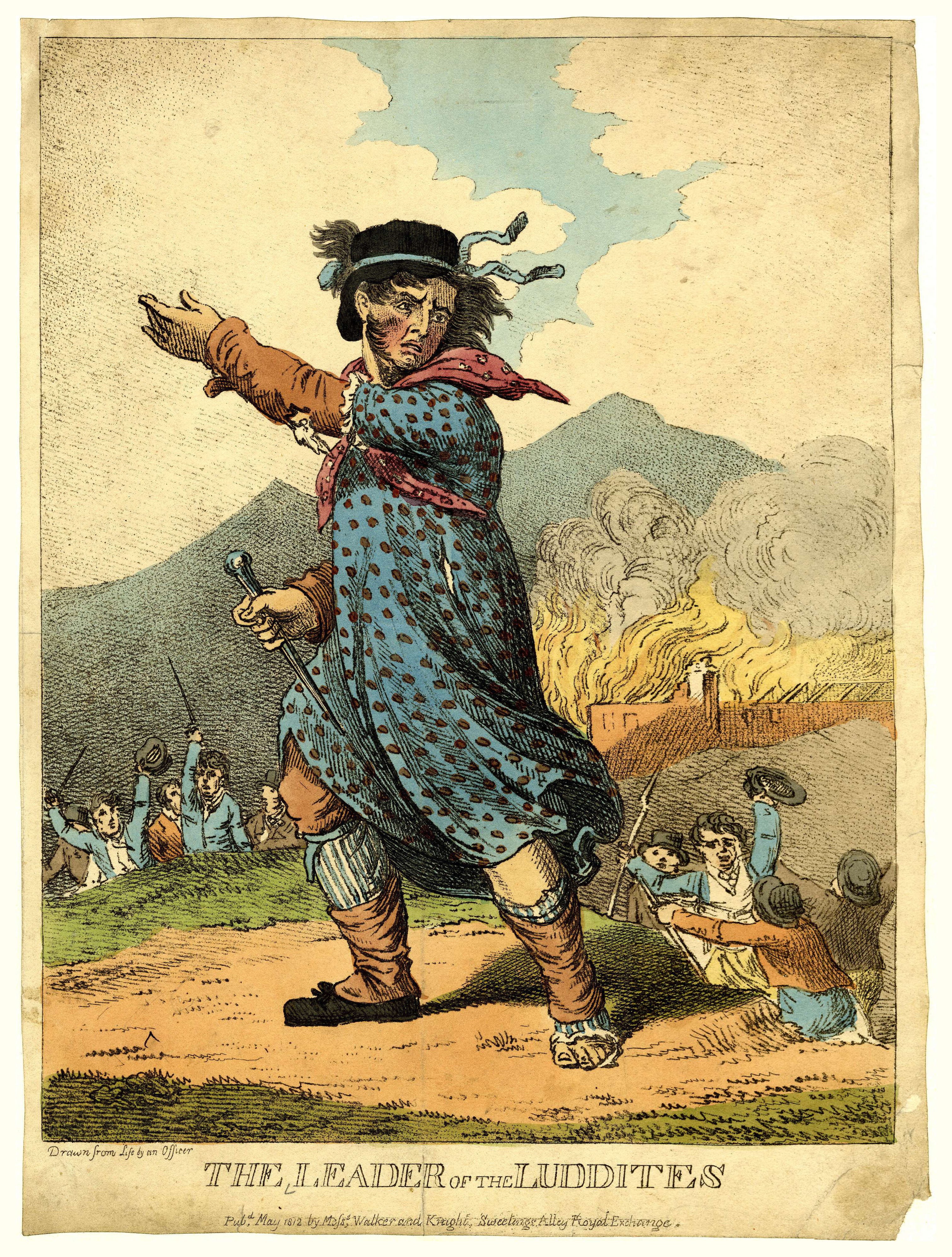

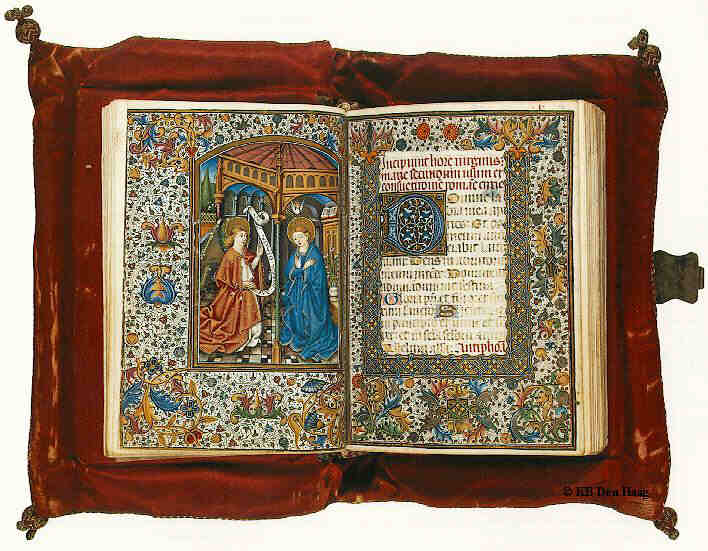

|

| One of the first images that Google brings up for 'Luddite.' |

Of the more respectable online dictionaries, Merriam-Webster offers a typical

definition:

: one of a group of early 19th century English workmen destroying laborsaving machinery as a protest; broadly : one who is opposed to especially technological change

This is the standard dictionary definition of the term, but this hardly encompasses the range of meanings the word has assumed. Other common uses of the word are summed up by

whatis.com:

1. A Luddite is a person who dislikes technology, especially technological devices that threaten existing jobs or interfere with personal privacy.

2. A Luddite is someone who is incompetent when using new technology.

By the first definition, an author who still prefers a manual typewriter can be called a Luddite; more specifically, a projectionist who sees his job threatened by "foolproof" digital projectors is also a Luddite. By the second definition, your Grandmother who can't program her VCR is a Luddite (for that matter, the fact that she still uses a VCR also makes her a Luddite).

So aside from the historical Luddites, a Luddite can be someone who is opposed to technological change, or is against technology that threatens people's jobs, someone who is technologically incompetent, or merely someone who dislikes technology. But wait, there's more...

From the user-contributed

Urban Dictionary:

1. One who fears technology (or new technology, as they seem pleased with how things currently are...why can't everything just be the same?)

2. A group led by Mr. Luddite durring [sic] the industrial revolution who beleived [sic] machines would cause workers [sic] wages to be decreased and ended up burning a number of factories in protest

A luddite [sic] generally claims things were "just fine" back in the day, and refuses to replace/update failing equipment/software/computers on the basis that they were just fine 10 years ago.

So according to this person, Luddite is synonymous with

technophobe, as well as referring to the type of stick-in-the-mud who still runs Windows 95 or listens to 8-track tapes (depending on the age of the "Luddite" in question).

This assortment of definitions encompasses such a broad range so as to render the word fairly meaningless. This is evident in some of the usage that Google turned up. For example...

A British politician commenting on

Prince Charles' concerns about genetically modified food:

It's an entirely Luddite attitude to simply reject them out of hand.

An American politician commenting on George W. Bush vetoing a

stem-cell research bill:

This will be remembered as a Luddite moment in American history, where fear triumphed over hope and ideology triumphed over science.

The bloggers

Bottom of the Glass have offered their own definition, accompanied by the cartoon below:

Luddites are the Amish. They are anyone who, at any point in time, drew a line and determined that all technology and modernization up to said point was acceptable while all of it beyond said point was evil, deplorable, of the devil, whatever. They are people who bury their head in the sand and wish new things would just go away...The goal of the Luddite is merely to freeze time, freeze assumptions, freeze change. And they seethe and growl at those who attempt to move things forward.

So which of these definitions/usage is the most accurate? And what does any of this have to do with the folks that smashed and burned textile machinery in England two hundred years ago? Perhaps we would do well to learn a little more about...

The Historical Luddites

[Note: The following information comes from a smattering of websites I perused, some of which can be found

here, as well as the old standbys of Wikipedia and Brittanica Online, but my chief source was historian Kevin Binfield's site

Luddites and Luddism: History, Texts, and Interpretation.]

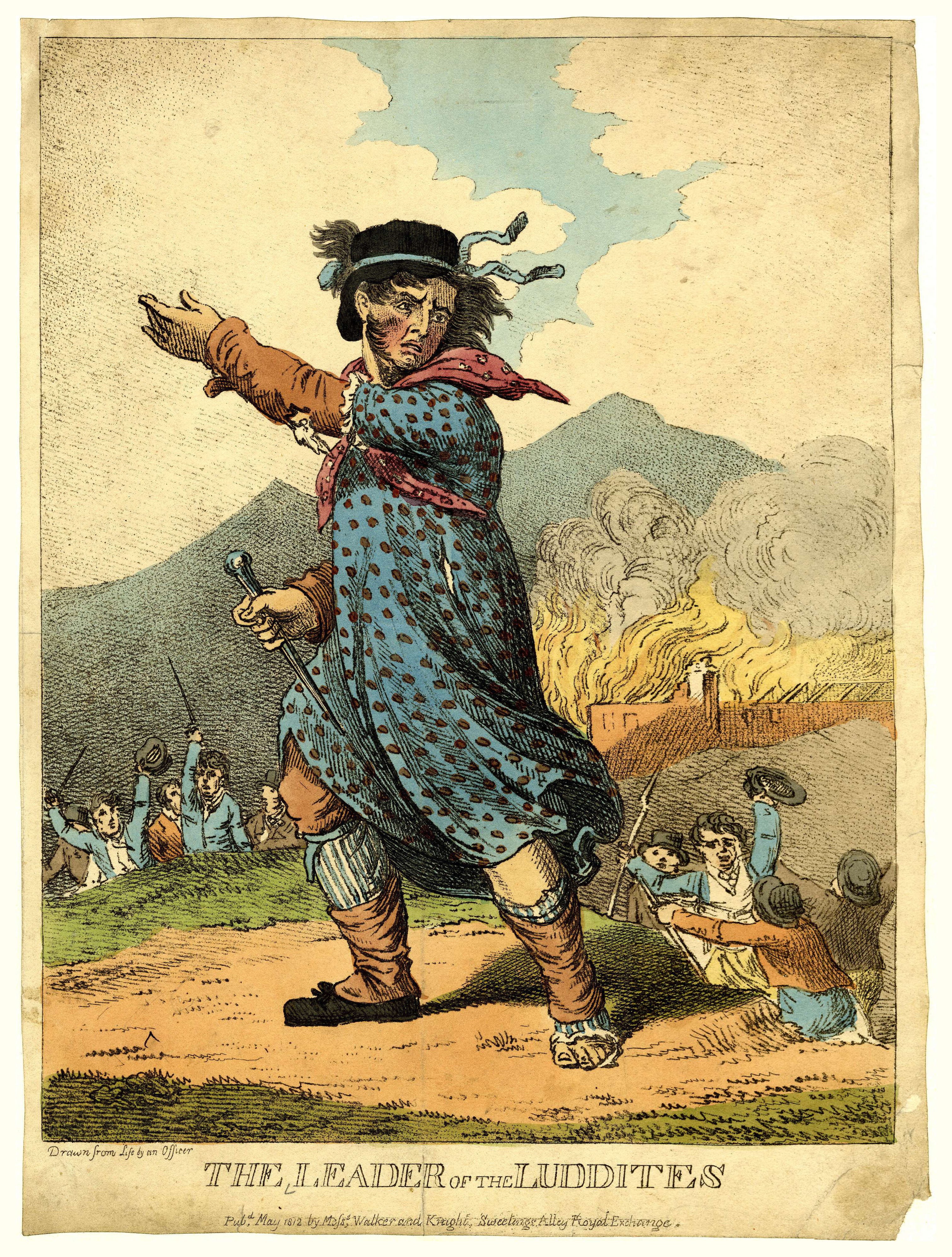

|

| Frame breaking (1812) |

On March 11th, 1811, a bunch of Nottinghamshire stockingers (skilled artisans who knitted stockings) gathered to protest lowered wages, rising food prices, widespread unemployment and the hiring of unskilled laborers, as they had (peacefully) many times over the previous month. This particular evening's meeting ended with a bunch of the stockingers smashing the wide-frame looms (a semi-automated knitting machine that could be used by unskilled laborers) at a local shop which epitomized their grievances. This sparked a frame-smashing fever in the area, and the Nottingham Journal reported several weeks of nightly frame-smashing throughout villages in Nottingham County, as well as arson and other forms of vandalism directed a

t textile mills. A typical account from the time relates that, "2000 men, many of them armed, were riotously traversing the County of Nottingham."

|

| King Lud. |

These stockingers were not, as the misinformed user of Urban Dictionary claims, "led by Mr. Luddite;" but they soon began to began to be known as Luddites because the frame-smashings were usually attributed pseudonymously to one Ned Lud. According to the

Oxford English Dictionary, the real Ned Lud was a fellow from Leicestershire who, in 1779, had destroyed a stocking loom "in a fit of insane rage." We don't know much more about the guy than that, but people had apparently remembered his act of senseless destruction enough that "Lud must have been here," had become a catchphrase used whenever machines broke down. By late 1811, letters full of demands were being sent to textile mill owners and local papers signed by "Ned Lud," "General Lud," "Captain Lud," or, most famously "King Lud." The character began to evolve into a Robin Hood-like folkloric figure. Protest leaders began dressing in outlandish getups as "King Lud" and claiming to be King Lud, while the crowds shouted treasonous chants such as, "No King but Lud!"

Luddite protests, riots, and acts of sabotage spread from Nottingham County throughout the English Midlands, as well as spreading to related industries such as cotton manufacturing. This continued in sporadic bursts through 1816. A few of the Luddite demands were met (certain trade restrictions were rescinded, moderate wage increases were gained for some and food prices lowered slightly), but for the most part they met with stiff government reprisals. The Army was dispatched to quell Luddite riots, and for a time there were more British soldiers engaged with the Luddites than there were fighting Napoleon. In 1812, Parliament passed an act which made all industrial sabotage or "machine breaking" a capital offense. In 1813, seventeen Luddites were executed under this act and several hundred more were transported to the penal colonies in Australia and Tasmania. Three more men were executed for the murder of a mill owner later that year. The movement began to falter quickly thereafter.

The conventional telling of these events holds that the machines destroyed by the Luddites were new technology and thus perceived as newly threatening. The notion that the Luddites rebelled against a new innovation is central to the way the word is typically used today. This, however, was not the case. The

stocking frames which the Luddites were smashing had been invented way back in 1589. Fearing that the invention would cost English stockinger jobs, Elizabeth I and James I had banned the machines in England, but from the 1660's onwards they had been playing an increasingly large role in the British textile industry. By the time the Luddites began smashing them there were over 25,000 of the machines in place in Nottingham County, and most of them had been there for many years.

So what provoked the Luddites in 1811? Essentially, there had never been a worse time to be a trained stocking-knitter in England owing to a whole host of factors. The mechanized stocking-frames had been putting skilled artisans out of work and driving down pay steadily for 200 years, but in the first decade of the 19th century several more blows came all at once. The first was this guy:

The Napoleonic Wars forced Great Britain into a massive depression from 1808 onwards. Hardest hit were those that produced commodities. Since Parliament had relented to pressure from the nation's wealthiest to eliminate the income tax, the only way to pay for the war was with high commodity tariffs and taxes as well as increased fees and sales taxes. The burden of all this hit the working classes the hardest. The government also attempted to get back at France by banning trade with them and all countries friendly to France (much of Europe, especially as Napoleon conquered more). This meant no foreign markets to sell textiles in.

As the wars dragged on, Britain began to recall its Army and focus its efforts on its navy and on subsidizing foreign allies, adding to the already sky-high unemployment when hundreds of thousands of soldiers returned to England in need of work. Wartime food rationing, several years of crop failures as well as price-support laws designed to protect farmers led to food prices being at an all-time high just as wages and employment were at an all-time low.

The hardships brought by the Napoleonic Wars also came at the culmination of several centuries worth of economic and social change as the English economy shifted from Mercantilism to Free Market Capitalism, and as the Industrial Revolution continued to gather steam (no pun intended). Once upon a time, knitting had been a prime example of a

cottage industry, where skilled artisans worked from home. Stockingers, like all skilled artisans, typically served an apprenticeship of seven years (as required by law). The introduction of automated machinery in the mid-1600's meant that mill owners could get away with hiring unskilled workers for dirt cheap, rather than paying apprenticed artisans the wages they demanded; however, for just this reason trade guilds successfully petitioned politicians to write laws requiring workers in traditional trades to serve their full apprenticeship and requiring mill owners to hire apprenticed artisans. With the expansion of colonialism (and thus the demand for goods and availability of resources), the textile industry shifted slowly from a cottage industry to the

factory system in the 18th century. However, even though textiles were now made in factories using machines such as the stocking frames, it was still mostly skilled artisans who were doing the work, thanks to government protection and legislation as well as the influence of the trade guilds. Additionally, the economy was still largely a controlled Mercantilist economy with prices stiffly regulated and wages protected by orders of Parliament and the Privy Council.

At the turn of the 19th century this old economic system was breaking down and the tightly controlled economy of years past was giving way to modern free market capitalism. By the time of the Luddites, laws concerning price and wage regulation had been revoked, and mandatory seven year apprenticeships and required hiring of artisans were also no longer in place. The invisible hand of supply and demand now ran everything, and Britain's labor force shifted to being largely composed of hired unskilled laborers. With the economic hardships brought by the Napoleonic Wars, milliners were forced to cut costs wherever they could, typically by slashing wages, and purchasing more machines so that they could hire unskilled laborers rather than skilled ones.

The Luddites were skilled artisans who had gone through seven years of apprenticeship only to find that they were for the same jobs as thousands of unskilled day laborers. These jobs had wages so low that, with rising food prices and widespread famine, it was increasingly hard to avoid the

Work House. This is what they were protesting. They were not technophobes, but labor organizers. The industry was scattered enough to make something like a general strike difficult and impractical if not impossible; destroying machines was one way to make their demands heard and assert some leverage over their employers. It was an example of what historian

E. J. Hobsbawm calls "collective bargaining by riot." This is well-evidenced by the various texts left by the Luddites; machine-smashings were always preceded by letters making specific demands about wages and hiring practices; the milliners who met those demands (and a fair number did) did not have their machines destroyed.

It is especially worth noting that the Luddites were hardly the first to smash machines for this reason. Industrial sabotage has a long and illustrious history. As Kevin Binfield

points out:

For example, in 1675 Spitalfields narrow weavers destroyed "engines," power machines that could each do the work of several people, and in 1710 a London hosier employing too many apprentices in violation of the Framework Knitters Charter had his machines broken by angry stockingers. Even parliamentary action in 1727, making the destruction of machines a capital felony, did little to stop the activity. In 1768 London sawyers attacked a mechanized sawmill. Following the failure in 1778 of the stockingers' petitions to Parliament to enact a law regulating "the Art and Mystery of Framework Knitting," Nottingham workers rioted, flinging machines into the streets. In 1792 Manchester weavers destroyed two dozen Cartwright steam looms owned by George Grimshaw. Sporadic attacks on machines (wide knitting frames, gig mills, shearing frames, and steam-powered looms and spinning jennies) continued, especially from 1799 to 1802 and through the period of economic distress after 1808.

There were many similar revolts after the Luddites as well, including the

Pentrich Uprising of 1817 (a demonstration of several hundred unemployed stockingers, quarrymen and iron workers) and, most notably, the

Swing Riots of 1830-31. The Swing Rioters were farm laborers struggling against cripplingly low wages who destroyed threshing machines and threatened those who had them in order to make their demands heard. Like the Luddites, the Swing Rioters sent pseudonymous letters signed by a mythical "leader" of the revolt, in this case the entirely fictional

Captain Swing. Some samples from the letters:

Sir, Your name is down amongst the Black hearts in the Black Book and this is to advise you and the like of you, who are Parson Justasses, to make your wills. Ye have been the Blackguard Enemies of the People on all occasions, Ye have not yet done as ye ought,.... Swing

And...

Sir, This is to acquaint you that if your thrashing machines are not destroyed by you directly we shall commence our labours. Signed on behalf of the whole ... Swing

On an unrelated note, Captain Swing has recently been reborn as a steampunk master criminal who can spontaneously generate electricity and fights space pirates (or something) in a

comic book by Warren Ellis. He also lent his name to a bizarre 1960's Italian comic book (

fumetti) and an even more bizarre

Turkish film adaptation.

|

| I'm not making this up. |

Anyways, returning to my original query, the question remains: How did we get from a 19th century labor revolt to the modern usage of the word?

How the term 'Luddite' was transformed

I believe the main reason why the Luddites, out of the many industrial saboteurs and machine-breakers throughout history, have been singled out as an example is that there is a specific word to refer to them. In the grand scheme of history the Luddite riots were not all that unique, but talking about the "Swing rioters" or "the 15th century Dutch workers who protested new automated looms by throwing their wooden shoes into the machinery" just isn't as direct as saying 'Luddite.'

As near as I can tell, the endurance of the term is due mostly to neoclassical development economists, who seized upon the Luddites as a rhetorical device that could be used to illustrate something they termed the

"Luddite Fallacy." According to these economists, the "Luddite Fallacy" is the mistaken belief that labor-saving technology will lead to fewer jobs. I believe this seriously oversimplifies the actual history of the real Luddites, but it has been an effective enough rhetorical example that anyone from the early-20th century onwards who has taken an Econ 101 class has encountered the term. This kept the word 'Luddite' circulating in the language and perpetuated the oversimplified story of the Luddites as people opposed to new technology.

From the economists the term Luddite was transmitted to the college radicals of the 1960's, some of whom began to identify themselves as

Neo-Luddites. The sixties were a time when many leftist and anti-establishment groups happily claimed to be modern-day heirs to the Luddites. Neo-Marxists came closest to the original Luddites' aims, praising the workers for seizing the means of production, and Neo-Leninists and Anarchists praised the Luddite vandalism as 'propaganda of the deed.' However, those that most successfully adopted the term (or had it derogatorily applied to them) were those with objections to technology.

It was a great time to be anti-tech: the hippie counter-culture was in full swing, the conformism of the 1950's was seemingly embodied by new technology such as television and home appliances, and the Cold War threat of nuclear holocaust and the napalm bombings in Vietnam were on everyone's mind. This was the era that saw the flowering of such schools of thought as anarcho-primitivism and environmentalism. The admiration Thoreau and Emerson felt a century earlier for "nature unadorned" was being echoed throughout popular culture; it was a time to "unplug" and "get back to the land." 'Luddite' became firmly cemented in the English language as centrally relating to technology. The economic and social hardships being fought by the original Luddites were all but forgotten. The important thing to remember was that they smashed machines.

|

| Neo-Luddite. | | |

|

The Next Frontier for Luddism

And so now we have the word as used today, with about eight different varying definitions, all in agreement that a Luddite hates new technology, something that was not necessarily true of the original frame-smashers. With this ambiguity in language, I think there may be currently a new type of Luddite arising: the Language Luddite.

The English language used to be (at least, from the 1600's on) in the hands of the few and the highly trained, like the skilled and apprenticed textile artisans of old. These were the English professors, professional grammarians and the dictionary editors. It used to be a big deal when the staff of the Oxford English Dictionary added a new word due to common usage, or changed a definition owing to officially recognized shifts in language. It might still be a big deal, if anyone still consulted the Oxford English Dictionary for reasons other than trying to sound smart. But they don't.

|

| The OED: Helping people sound smart and needlessly lengthen research papers since 1895. |

Just as the economic climate of the textile industry had been shifting for some time before the Luddites, language snobs have always been fighting a losing battle against constant shifts in "proper" language use (as chronicled in Jack Lynch's bestselling

The Lexicographer's Dilemma). But language police today face something as catastrophic to them as the Napoleonic Wars and repeal of protective legislation were for skilled stockingers: the Internet.

Dictionary, thesaurus and reference book sales have been plummeting in recent years, thanks to the Internet. No Dictionary, not even the "Unabridged" varieties, could ever hold every word, but the Internet comes as close as anything yet. Besides, why would you need to own a dictionary when you can just use a search engine for the word and find dozens of definitions from dozens of sites? You don't even have to spell the word correctly; Google will still know what you mean.

The old standbys such as the OED, Merriam-Webster's and The American Heritage Dictionary are all online for free. But like the 19th century artisans, these reputable old institutions are competing with hundreds of non-professional, user-contributed sites such as Wiktionary, Whatis.com or Urban Dictionary. Also due to the Internet, the print business is in a slump, publishers and newspapers are cutting staff, especially editors (they'll always need people to produce content, but any computer can do a spellcheck), and serious journalists compete with bloggers. Those who would seek to maintain an iron grip on the purity of language are in dire straights. Just Google "all right or alright" and have a look at today's intense lack of consensus over how to properly speak and write the English language.

There must certainly be many language purists who are attempting to resist the changes being wrought by the Internet. The widespread confusion over a term like 'Luddite' must irritate them to no end. Surely, if anyone deserves to apply the term Luddite to themselves, it would be these "Language Luddites." Of course, they never will. They have too much respect for the term in its original and specific context.